Thumbnail photo source: T. L. Vincent and J. L. Brown, Evolutionary Game Theory, Natural Selection and Darwinian Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

✨ Hi! Welcome to my writing space and thank you for being here.

I'm Eshaal, a 19-year-old based in NYC who's interested in medicine, society/self, and international affairs. I'd love to hear your thoughts as well, so feel free to message me!

Table of Contents

What is Game Theory?

Do you ever walk into an interaction with someone and feel like you're in a minefield?

Or perhaps you're just going with the flow, wondering where it will turn up. That's a benefit we have on an interpersonal level; most of the time, you will not fear that the person you're speaking to has something against you.

Unless you're accustomed to the cutthroat, the political, and even the group project square-offs. Some interactions call for great strategy. In international affairs, you ALWAYS need great strategy... a fundamental theory in realist politics is the fact that you can never trust any state but yourself to defend you, even if they promise to. You must expect defection at any moment.

The way we map two-person problems isn't just a guessing game of behavior, either. It's... MATHEMATICAL!

Yes, math in politics. It's a social SCIENCE, people.

When running a cost-benefit analysis, actors are likely to prefer certain outcomes. They may calculate that even if they don't cooperate with you, they are better off. Or, they may decide that if they don't cooperate with you, they are definitely cooked. Maybe there's a case where, in the long term, you'd be better off working with somebody (e.g., splitting a slice of cake fairly to keep everyone happy and friends with you, wherein you can extract from the benefits of such friendship), but have a greater personal gain in the short term (eat most of heck before anyone else can, satisfying your cravings... technically, everyone's mad at you, but you did better for yourself).

We map these preferences and two-player games using game theory.

3 Models of Two-Player Coordination

If you're going to play a game, you have to know what game you're playing in the first place, and that will depend on how much incentive there is to defect in a given situation.

1. Prisoner's Dilemma: You Have More Incentive to Not Cooperate

Ahhh, the classic. Let me set the stage! You and a buddy are being questioned for a crime (that, for the record, you both totally committed). The questioner cuts you two the following deal:

Here's how we interpret the chart. If you were to order the preferred outcomes for YOU (forget your morals for a second; in a real-world international politics case friendship is not magic), they would go from the option with the least jail time to the one with the most. The best possible scenario is for you to throw your friend under the bus while they don't. This is followed by neither of you squealing, which is again followed by both of you squealing. The worst case is if you don't squeal and they do, because you get the highest sentence of 3 years.

In other words... if you're looking at this from a probability perspective, you're more likely to get a better outcome if you squeal, REGARDLESS of what you think your friend will do.

In international politics, we might compare this to the question of whether a country will develop a particularly destructive weapon even if there's an agreement with a neighboring nation not to. While it's nice if no one defects (aka develops the weapons anyway), there is a greater harm for you if you were the one to cooperate while your neighbor defected. Why put yourself in a situation where they have the weapon and you do not? Even if you break the agreement, it is better for your own security to just have the weapon. There is an incentive to defect, to be selfish.

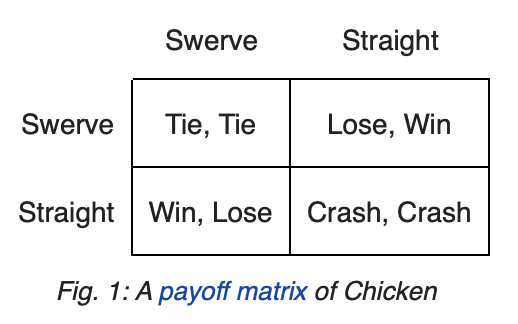

2. Chicken: Someone Has to Bite or We All Die

This might just be the most straightforward case. Let's say you're in a car, and there's another car coming straight for you. Obviously, someone HAS to move or you'll both crash (unacceptable cost!).

But, if you're the first to swerve to safety, you'll be labeled the chicken. Obviously this is preferable to death. But it's still ideal if you both come to your senses and swerve at the same time... that way, nobody has to be the chicken, and no one dies.

Here, you are better off for cooperating. No doubt about it. But this is the kind of game where testing how far you can go to scare the other person is a risk that can have great rewards.

The best real world example of this is brinkmanship with nuclear weapons. If a nation fires a nuke and another nation fires back, then you've just created an armageddon scenario with no victory. Someone will have to bite before it escalates to that point. However, getting CLOSE to the brink can scare your adversary into giving into your demands, which is a crazy risky but high-payoff scenario if it works.

Still. In select cases, there is no winning if you don't listen.

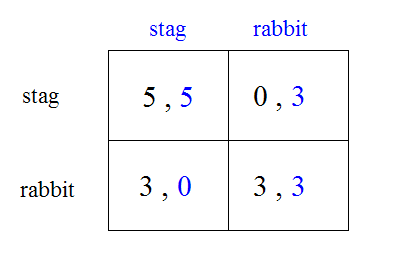

3. Stag Hunt: Weigh Your Gains

We all know what a stag is, yeah? Giant antler-ed animal? This game can be illustrated by the scenario of cooperating with another hunter in the woods to try and get that stag.

But you, the hunter, also see two hares. Meaning, you could help your fellow hunter with killing the stag and having SO much meat for everyone, or you can defect and go for the hare to fend for yourself... though a hare in its whole has less meat than the share of the stag you would have had.

Here, the order of preferences is for you both of you to cooperate, both of you to defect, you to defect, and least wanted of all, for the other to defect. In this case, you are definitely better off cooperating!

The problem that presents here is your own mistrust of the other hunter. What if they defect? Then they get meat and you don't, because you cannot kill a stag alone. Even though it is preferably, and perhaps even likely, that you'll both cooperate, there is an uncertainty/fear that may make you fend for yourself anyway.

There are many parallels of this in politics, such as between social responsibility and personal security in an enlightened society. This is ESPECIALLY depicted by our climate agreements today. Everyone is better off for cooperating because everyone will benefit from cleaner, healthier, more usable common-pool resources like air and water. However, because some nations will have better economic gains if they don't, they can still defect for a short-term goal, ESPECIALLY if there isn't a credible reason (to them, anyway) to believe others will comply. After all, if you comply and others don't, you're still the one at a loss.

One way to mitigate the mistrust that underscores this game is to create collective organizations and agreements with incentives to comply. The biggest case for organizations like NATO, the COP conferences, and even economic entities like the IMF is that they increase linkage between different issues (e.g., weapons proliferation policies will affect economic agreements) and increase the number of times nations interact in a constructive, cooperative manner (this is called iteration). This arguably increases cooperation overall.

Yet there is no world where a nation will not prioritize its security. The agreements that work best are the ones that benefit both the actor and the common problem at the same time, like when aerosols that were more eco-friendly tuned out to be less expensive for companies to make, leading to an effective repairing of the ozone layer that harmful aerosols once caused. Unfortunately, this is an ideal scenario, not the norm.

Wow, That Was Depressing

I know! Welcome to Political Science!

Kidding. While it is true that many real-world cases involve incentive stories defect from common goals, including climate cooperation, understanding the reasons for defection can really help actors find ways to incentivize cooperation instead. If you can conceive that a bad actor trying to proliferate dangerous weapons is actually concerned for its safety against a powerful neighbor, then perhaps addressing those security concerns is the route to stability.

And in typical philosophical fashion I will also ponder what this may mean for our own lives. It is diminutive to see your interactions with others as a game. Yet in some fascinating way, it helps to conceptualize that many decisions aren't made out of malice, but rather a shared fear for one's own safety, a predicament better understood by stepping into the other person's shoes. That's valuable to remember in all fields.